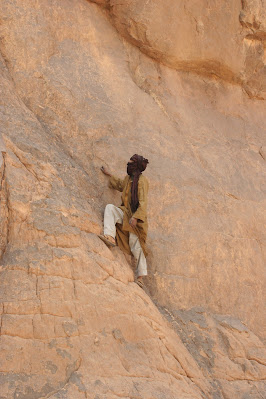

The next day, we rounded the northern end of the Tefedest Mountains and approached the base of Jebel Djanoun (above). At 2300m it would be a good two hour climb from our level at 1000m, so instead Leon and I tackled a smaller peak which Djafar named "Jebel Tourist" in our honour.

We crossed a wide section of piste running North-South, that Djafar said is used by cigarette smugglers. Then we reached the main road that links Tamanrasset to the North, and Djafar paid a short visit to a lonely mosque at Sidi Moulay Lahsene. Following tracks 20km to the West, he brought us to the best camp of the whole journey. The area has mountains of smooth grey volcanic rock, steep sided with rounded tops. I don’t know the geology, perhaps volcanic extrusion, but the shapes are not unlike Ayers Rock.

The volcanic hills at Tesnou - for scale, note the Land Rover above and people below

My Favourite Sahara Camp

On the fifth day of the journey from Djanet to In-Salah we had another first, as Con lifted the food box to disturb a pale scorpion who darted away under the car. It was an easy run up 120km of tar to Arak where we could refuel and water. The only shop had very little fresh food, but we got potatoes and stocked up with luxuries like yoghurt and sugary chocolate. Then we had our last section of Sahara piste, turning off just North of Arak onto part of the old Hoggar route. There was plenty of security around in Algeria, and at Tadjemout we were intercepted by an army pick-up. The whole oasis was swarming with soldiers, even up the trees and behind rocks in the hills behind. Djafar waved the magic piece of paper – and on we went.

Maybe after a lot of desert we were getting jaded, but I found it a rather boring route, wind-blasted and tiring. We have been gradually descending for the last couple of days, and it is hotter again, almost 40C. As the piste has been superceded by a tarred road that runs to the West, it is no longer maintained, so every time we got to third gear we’d find the track washed out and would need to slow and crawl over boulders. We spotted a couple of gazelles, dancing away across the rocks.

Our best camp was followed by one of the worst, windswept and insecty, a bad combination. Giant camel spiders (solpugids) scuttled around. But even that camp was better in the calm of morning, and I’d rather be in the desert than any of the towns. For reasons unknown, it seems that Djafar set fire to the nearby oasis grass.

As we got closer to the tar again we met Haakon returning at speed. He’d heard gunfire ahead, and soon we could hear it too, heavy machine guns and explosions. The most likely explanation was army exercises, and Djafar agreed – he knew there was a base a little ahead, and waved us on. However, he got a severe ticking off from the army once we reached their checkpoint. He wasn't intimidated, and brandished our fiche, which includes the route as registered with the Gendarmerie. I suppose the army, and most Algerians, cannot understand why tourists would want to travel a washed-out old piste when there is a nice tar road instead. But with thousands of square miles of desert you’d think they’d find somewhere else to practise, not near a tourist route, no matter how few we are.

In-Salah: A helpful list of some of the worst towns in North Africa (Tamanrasset excepted)

At In-Salah, Mohammed Haffaoui of Tanezrouft Voyages entertained us in the courtyard of his home, reclining on cushions and carpets. The delicious meal of salads, couscus, mutton and sauce was prepared by one of his wives, a native of Timbuktu. We treated ourselves to the best hotel in town, probably the only place for a thousand miles that serves beer.